“Baseball breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart. The game begins in spring when everything else begins again, and it blossoms in the summer, filling the afternoons and evenings. And then as soon as the chill rains come it stops and leaves you to face the fall all alone, when you need it most.” —A. Bartlett Giamatti, Commissioner of Major League Baseball, 1989

My father teaches me two essential skills at the tender age of eighteen months: to read and to blow raspberries with my tongue anytime I hear a mere mention of the Mets. He is twenty-seven years old and agile. I am his first child. He has the time and energy and patience to burn, and these are the skills he has armed me with.

Meandering around our apartment in Brooklyn, I wear pinstriped short sets and perpetually mumble about apple juice and Yankee baseball. I have a propensity for falling without putting my hands out to catch myself. I suffer incidents that leave me with a series of stitches across my bottom lip.

He feels tremendous guilt, longs to be Yogi Berra in the rye. I scream when the doctor moves in to mend me, and my father takes my tiny hands in his and tells me it’s just stitches, it’s just stitches like on a baseball.

I get older and marginally more graceful. He moves me to the suburbs of central New Jersey, leaving behind the borough he’s called home his whole life. He wants me to have grass. He buys the house with the biggest backyard on the block and we run around with whiffle ball bats, affecting Phil Rizzuto accents—holy cow!—the day we move in. It’s our own Field Of Dreams. He is Ray Kinsella and I am baby Gaby Hoffman before she chokes on a hot dog.

In our new house I sit on the pristine blue carpet in front of the television stringing shells on a yarn necklace while my father sits on the edge of the couch. He tells me I could learn tonight how baseball history is made.

Jim Abbot, the Yankee pitcher born with one arm, is about to complete a no-hitter. And when it happens, my father swings me wildly around the room and we dance like mad, echoing the excitement of the ballplayers and the sportscasters on the screen. The electric of the September evening ignites something in me. It feels like a fever breaking.

*

My brother is born two years after me and everything about him is just a beat swifter, sweeter, better. In New Jersey, we both play little league, but he makes the all-stars and the travel team at the tender age of seven. Our family follows him around the state and I become intimate with the landscape of every little league complex in New Jersey—the cheese fries in Lincroft, the swing sets in Flemington, the lime rickeys in Edison.

Everyone forgets that at just four years old, dressed in a green thermal dress and cowboy boots, I hit a baseball off the tee from the top of our driveway and onto our neighbor’s roof across the street. It was a home run—the sort Mantle used to hit some laughable, nonsensical length outside the ballpark. My brother the all-star could barely get his bat on the tee-ball. I remind my father of this sometimes.

“You’re the most naturally gifted hitter in the whole family,” he tells me in earnest. It is a concession that makes me beam, before his stipulation robs me of any resonant joy: “Your brother has an unrivaled work ethic, though. He works hard, that’s why he’s doing so great.”

My resentment manifests itself in the fantastic wish to become my brother in a spell I’ve crafted in my mind. But for the most part, we get along famously. And although we are unconsciously, unfairly pitted against each other sometimes, it is not enough to stop me from wanting to be his best friend.

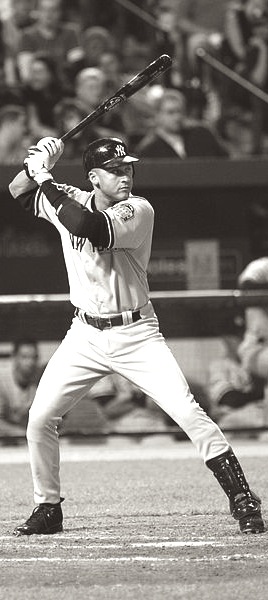

Baseball is the experience we share, the common thread between us that ousts DNA as the tie that predominantly binds. When we go to Mattingly’s last game we keep careful score together. When the Yankees win the World Series for the first time in eighteen years, my father pours a bottle of champagne over both our heads. When we visit the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown for the first time, he picks out a present from the gift shop for me: an enormous black and white poster of my beloved Derek Jeter’s rookie face.

My desire to become my brother subsides only to resurface with ferocity. Such is the case the night our father takes us to a historic game on a rare school night. It is the first game ever between two Japanese starting pitchers and is being broadcast nationally and simultaneously in Japan. We have third row seats on the third base side. In the second inning, Derek Jeter cracks a foul ball that lands squarely in my brother’s glove. The television cameras pan over to catch a shot of him dancing the dance of the happiest seven year old on earth, alongside his proud father and his jealous older sister. My grandmother captures the moment on a VHS tape that documents my look of envy for all eternity—a look broadcast to the entire country, and to all of Japan.

*

I meet the first and last blonde-haired, blue-eyed boy I’ll ever fall in love with in a scorekeeper’s booth at a little league game. I don’t go up there looking for trouble—just for a quiet place to tear through my bounty of Italian ices from the concession stand—and there he is. His brother is on my brother’s team. He is a couple years older than me, on the edge of his freshman year of high school. I am a skinny, snaggle-toothed eleven year old dressed in my everyday uniform: a backward purple Yankees cap and a Derek Jeter 1998 World Series jersey.

“Jeter’s my favorite player, too,” he says, like we know each other or something. I stand there with the tiny wooden paddle spoon in my syrup-stained mouth like a sucker until he pulls out the rusted folding chair next to him and offers to teach me how to keep score.

He’s keeping count of balls and strikes and I’m in charge of advancing the innings and adding runs when someone crosses home plate. I am drunk on power and rainbow ice and the smell of the department store cologne emanating off the beautiful boy to my right.

“What are you listening to?” he eventually asks, tilting his chin towards my Discman.

“It’s ‘If You Steal My Sunshine’ by Len. What do you listen to?”

“Eminem, a lot of rap. Do you like rap?”

I glance self consciously over to my zipped up sleeve of CDs, boasting a mortifying mélange of Ricky Martin and Jennifer Lopez’s debut albums, Madonna’s Immaculate Collection, the Austin Powers 2 soundtrack, and some early Britney Spears.

“Totally. I love Eminem. He’s one of my favorites.” I have been in love for six whole minutes and I’m already compromising myself.

I begin looking forward to the games that once bored me to tears. Wanting to see him is exciting and excruciating, like waiting for opening day in the final stretch of a bone cold winter. When there are no games, I pass time carving the number he wears on his jersey into wooden surfaces with my nail and listen to “Waiting For Tonight,” summoning images of his face.

With passing baseball seasons his name will fade like chalk in the dirt along the baselines. But he is the reason I am conditioned to believe all love somehow happens just this way: smelling like grass and sweat and concessions beneath the night sky of the hazy mosquito summer.

*

At college, I learn it takes me only three days to fall in love. That’s how long I had been dating the Dodgers fan with the perfect teeth when I cry to my roommate that I either need to be with him for the rest of my life or I need him to cease to exist.

He is the reason I have reconditioned myself to believe all love happens just the way it happened for us: in Boston, in the springtime, as all the flowers reawaken in the Common and the baseball teams come back to town. When our love boils over and incinerates spectacularly, I take the first train back to New Jersey. I long to sleep in my childhood bedroom, beneath my Derek Jeter poster.

My hometown best friend meets me at the diner on Route 9 at the behest of a cryptic text message I’ve sent him.

“So,” he says sliding into the booth across from me. “Are you a Dodgers fan yet?”

I’m staring deep into my tea like the leaves are going to rise from the bottom and spell out how to feign being cavalier. “I’m not dating a Dodger’s fan anymore.”

“Wait, you broke up?”

I am silent for a few minutes. The waitress comes by and sets a cup of tea down in front of him, then keeps an intrusive eye on me over her shoulder as she shuffles away.

“Well of course we broke up!” I finally yell, slamming a petulant palm down onto the table. “What did you think, that I was going to marry a fucking Dodgers fan? We got rid of those bums in ’57. I hate the Dodgers. I’m already over it.”

He raises his eyebrows. It’s clear to both of us that I’ve completely lost it. As always, he has the solution.

“Got any plans for tomorrow night at 7:05?”

We buy grandstand tickets and make our regular pilgrimage—the religious excursion to the Bronx in the springtime. It is the first game we ever attend at the new Yankee Stadium, and we walk through the gates in the shadow of the shell across the street, the stadium we grew up in.

From the grandstand we can see everything that happens, and the wind that whips across our faces is the wind that heals us no matter what we are suffering outside. This is a truth I have always known, but never had to lean on. And now I lean into it—the roar of the bleacher creatures, the trill of the organ, the smell of the Hebrew Nationals, the stickiness of spilled beer underfoot.

As I’m taking all this in, the original and most prominent boy of my youth steps up to bat. A recording of Bob Sheppard’s Godlike voice: number two, Derek Jeter bursts through the loudspeakers and my best friend shoots to his feet to applaud. He looks down at me, perched in my blue plastic chair, and bends low to get close to my face.

As I’m taking all this in, the original and most prominent boy of my youth steps up to bat. A recording of Bob Sheppard’s Godlike voice: number two, Derek Jeter bursts through the loudspeakers and my best friend shoots to his feet to applaud. He looks down at me, perched in my blue plastic chair, and bends low to get close to my face.

“I know you’re manically depressed and all that,” he whispers, “but as long as Derek Jeter is a Yankee we’re going to get on our feet and show him some respect.”

I rise wordlessly. I’m still standing, clapping absently, then manically, when the crack of the bat reaches my ears and we watch him tear down the baseline.

The crowd pours out onto River Avenue, into the cool fabric of the night with the sounds of Frank Sinatra blaring behind us. We salvage the springtime and I am back in the game.

*

“It is just like him to do this,” I hiss into the receiver. “He just had to do something to throw me somehow. I am the Ralph Branca to his Bobby Thompson.”

I wail it over and over, comparing us to the pitcher-batter pair responsible for the game ending “Shot Heard Round The World” homerun—the greatest triumph or upset in baseball playoff history, depending if you root for the Giants or the Dodgers.

My father—the one who spent hours reading books about the famed 1951 pennant race to me in my youth—is on the other end of this phone call. He appreciates the reference but respectfully disagrees.

“That’s just bullshit in every sense of the comparison. If anything, you are Bobby Thompson and he is Ralph Branca. And that analogy doesn’t even begin to cover it.”

I am disappointed with a recent string of conquests. I am supine on a long couch in my Boston apartment with an arm melodramatically slung across my face.

“If you’re going to let anything break your heart,” he tells me, “let it be baseball. You don’t have room for anything else to get to you this way.”

A week later I receive a letter from my father. It reads:

I have no doubt that you will be great. And that’s just it: you will not be good, you will be great. You are the Willie Mays to his Vic Wurtz—your glove is where line drives come to die. Thrive off the heaviness of your heart and take solace in knowing one day you’ll wake up and it won’t be so heavy anymore.

*

At Old Timer’s Day, Whitey Ford comes out onto the field in a golf cart and I start to sob. My boyfriend—a British citizen—is beside me, stacking a neat tower of souvenir beer cups.

In the two and a half years we have been dating, this is the first time I’ve managed to drag him to the Bronx and get him to feign interest in the sport that makes me whole.

Unbeknownst to him, we have entered what will be the final inning of our relationship. He’s recently made the last in a long string of mistakes that will result in my leaving for good.

I sip the stadium lemonade while he works on the beer. I’m trying to explain the Reggie game and the Dynasty and the gaping Old Timer’s Day void Bobby Murcer left behind and he’s being polite and pretending to care, but he’s only a mildly effective actor.

With Bernie Williams on base, Tino Martinez hits a home run off David Cone. The boys I screamed for in my youth are back on the field. I’m watching them round the bases, laughing in pinstripes, triumphantly making their way home.

My boyfriend leans in and kisses the side of my face. “I love you, you know,” he says into my hair.

He’s wearing the Mickey Mantle shirt my father bought me in middle school. “I know,” I tell him. “I love you, too. I love you beyond reason.” It’s the truest thing I can say.

Fishing for attention and reassurance, he puts his arms around me, pulls me into him. “I’m afraid you’re going to leave me for a Yankees fan one day.”

I let out a laugh, tilt my head back and stare at the curve of the frieze against the sky and I thank the good lord for making me a Yankee, just like Joe DiMaggio did.

“My love,” I tell him, turning to him, cradling his sweet face in my hands. “I’m not going to leave you for a Yankees fan. I’m going to leave you for someone who doesn’t fuck other women.”

*

When I move to Brooklyn from Los Angeles I offer a simple explanation for my departure: the traffic on the 101 is crushing my spirit and I long to be just a subway ride away from Yankee Stadium. And when springtime comes to the Bronx, more often than not I race from my desk to the 4 train to the stadium—just in time to see Derek Jeter take the field.

In New York, the men I meet in bars love to talk about baseball. I ask them to trade war stories with me—the best games we’ve ever been to, the time he met Joe Torre in a restaurant, the time I got into a physical fight with a fan in Boston.

The Phillies fan has me up against the wall in the corner of my East Village haunt, murmuring: I can’t believe I’m kissing a Yankees fan. The Red Sox fan has me dancing around his apartment to records, telling me I’m beautiful enough to question his allegiances. The Giants fan is answering my call just as the bar closes, listening to my 3 a.m. rasp: I’m just calling to say hey, Willie Mays.

I meet a Yankees fan who drinks whiskey with me and asks how my last relationship ended. I decide to give him the ultra condensed version.

“My boyfriend was very insecure. He kept saying, ‘Baby, I want you to love me as much as you love baseball.’ And I told him I’d never love anyone like I love baseball.”

He meditates on this for a moment, wondering if I’m some sort of dead end. But instead of turning around and backing away, he recites a bit of the monologue from the end of Field Of Dreams—the one about how baseball is part of our past, how it reminds us of all that was once good and could be good again.

I grip the edge of the bar like the railing of a long, steep staircase and say to him, “I would really like to kiss you now.”

And then I do.

*

I am in Florida for Yankees Spring Training—the first I’ve ever been to and the last Derek Jeter will ever attend, as he has just announced his retirement from baseball. The drive from our hotel in Sarasota to Steinbrenner Field in Tampa is a slow drip filled with narrow, congested roads. I drift off for a bit with my head against the window, lulled by the white noise of the car mixed with the sound of my father’s voice telling Billy Martin stories.

When I open my eyes, the last of the light has given way to a breezy darkness, and in the distance I can see the bowl of the stadium lighting up the sky. The streets are lined with baseball fans, residents selling t-shirts and bottled water, guards ushering cars into makeshift parking lots. When I roll down my window I can hear the roar in the distance. It feels like jumping into the pool for the first time after a long winter—the rush of cool water over your body as you remember: this is what it feels like, this is what my body feels like in the spring.

The caravan is reminiscent of that last scene in Field Of Dreams—all the cars lining up down the dark street so people can catch a quick, intimate glimpse of their heroes. Throngs of fans are walking three abreast across the long stretch of the footbridge into the stadium. The anticipation makes my insides chatter and the car barely comes to a stop before I jump out of it and onto the grass, calculating my shortest trajectory to the stadium.

Beneath the night sky, I’m carried towards the stadium on trembling legs—my pace quickening with each passing minute, until I am launched into a full sprint towards the field. And when I get there I inhale deeply until I am lightheaded, longing to preserve the scent of the grass and the concessions in my chest like a bottle.

I am leaning over the railing by my favorite spot in the stands, between home and third. My father strides up beside me, looks out onto the field and says, “Hope springs eternal. Don’t ever forget that you stood where you’re standing right now.”

And just as the calm washes over me, just as my body relaxes to let the spark of the evening run right through me, Derek Jeter springs out in front of me to take his place on the field looking like he did in those hopeful Bronx nights in 1996.

Courtney Preiss lives, writes, and mourns dead celebrities in Brooklyn. Her story “Life Ain’t Easy For A Girl Named Mickey” is the recipient of the 2013 Jim Palmer Baseball Writing Prize. She tweets @cocogolightly.