Like many, many others, we dived into the k-hole that is breaking down Breaking Bad. What follows is a series of gchat conversations between Jess Stoner and Carmiel Banasky about the show, its fiction connections, and our obsession.

[We start from the very first scene of “Blood Money“]

CB: I love this intro (I’m rewatching as we chat). It keeps with the pool motif. The pool has become a way to track the passage of time in the series.

JS: I know! It brings you right back to the first episode of this season…God, the matches into it, the plane crash, the everything. Although can I just say first: I AM SICK OF THE MONTAGES.

JS:

CB: I made a comment to the friend I was watching the episode with about that: here is the _____ montage.

JS: Ok, I’m over it. The Heisenberg written on the walls. I was like: SHUT THE FRONT DOOR.

CB: Yes! It got me so excited!

JS: Me too! In some ways, the show is basically a romance novel now. We “know” how it’s going to end, it’s just how is it going to get there.

CB: But we don’t know what’s going to happen, do we? Some people are convinced Walt will die…but maybe not? It was always WW on the descent, or at least the appearance of one, from “good dad” to “evil drug lord,” vs. his cop brother-in law.

JS: You’re totally right. I guess, do I even care? I mean, I care. But to me, this show felt “finished” from the very first episode—it felt like it knew where it was going. It reminds me of Henry James, what he talks about with his characters, them finding their way–although he always has the ultimate control. For instance, in the preface to The American, James wrote:

I seem to recall no other like connexion in which the case was met, to my measure, by so fond a complacency, in which my subject can have appeared so apt to take care of itself.

Vince Gilligan has said that even his understanding of Walt has changed, but it “feels” as if he always knew where he was going, which is exactly what James writes of later, about his character in The American:

With all these plans can it really be true that, ‘once the man himself was imaged to me (and that germination is a process almost always untraceable) he must have walked into the situation as by taking a pass-key from his pocket?’

In any event, I feel very sure that the writers wanted us to behave just as we’re behaving, looking for all the clues they laid out for us throughout the past 50+ episodes.

JS: I was watching the last episode of the first eight and got very drunk and was thinking: what happened with that company he was involved with so long ago? Maybe he never “broke bad,” maybe he did something bad with that company, the reason he had to be bought out? Towards the last drinks of the evening, I saw this huge connection between the Heinseberg of Breaking Bad and the Heinsenberg of Michael Frayn’s Copenhagen and the hints of him in Nicholas Mosley’s Hopeful Monsters, and the conflicting theories of Heisenberg: did he purposefully sabotage the bomb? Or was he just not good enough?

CB: Yes, which is the mask, which is the man? I think we are certainly supposed to make the connection between Los Alamos then, and Walt’s connection to it through his lost company. In the final stretch of this series we are, excuse the pun, waiting for a bomb to go off. And the uncertainty principle is one of those pop-culture terms that few understand but many want to use in their TV series.

CB: This episode made me remember what an amazing actor Hank is, without thinking of him BEING an actor in the moment. I love that Hank and Walt are fallible in totally different ways.

JS: Yes. And we can never forget Hank’s weakness for minerals.

CB: Hank has PANIC attacks. It’s wonderful and real, totally vulnerable.

JS: My husband HATES Hank’s wife. And I love her.

CB: I love her. And that she thinks Hank doesn’t want her to tell Skylar about his panic attack because of his pride.

JS: I’m really interested in if the ladies love Marie and if it’s a dude thing, this not liking Skylar and her sister. I know that Gilligan mentioned that the ladies hate Skylar too, but, ugh.

CB: I think Marie can be viewed as a cliché.

JS: Which is funny, because I have a sister and Marie seems very real (no offense to my hermana, Courtney).

CB: The cliché overreacting housewife, but I think she’s very relatable.

JS: She’s flawed, but she’s clean. Unlike pretty much everyone else now.

CB: Yes, she could be viewed as a moral center. But she’s also not forced to make the hard choices the other characters are forced to make. There was never a trigger for her to break-bad. She hasn’t faced death.

JS: I was telling my husband about our conversation and he mentioned that he thought her klepto problem was much bigger than ever revealed to us—that Hank was making it disappear. I wonder if it’ll come back?

CB: What’s brilliant is that the whole series OPENS with Marie shoplifting and breaking the law. It’s like that wonderful short story by Mona Simpson, “Lawns,” that begins with her confession to one crime (the first line is “I steal”) in order to distract the reader from the real issue.

CB: The series opens with this crime, which is nothing, compared to what happens next. But it opens with characters, motivated by flaws we haven’t seen much of in television; characters who are imperfect and in flawed relationships, to both set the stage and to distract us in a way.

JS: I keep thinking of Skylar in the first episode, watching her Ebay sales.

CB: And how she jerks Walt off on his birthday. Saying “This is all about you.” Haha.

JS: One thing about using the birthdays that works so well is that so few have gone by.

CB: Okay let’s go back.

JS: Okay, I’m grabbing another beer.

CB: At the car wash register, after Skylar asks about that strange woman (Laura) who just came in with a rental, the camera pauses on Walt. We’re waiting to see if he’ll lie. And he doesn’t. He’s so manipulative — it’s hard to tell if he’s telling Skylar just enough truth, or the full truth as a new general practice. And the power that she has reclaimed.

JS: I think Laura is going to come back and play a role this season. And while I was watching this episode, I kept thinking how tall Skylar seemed. But while she has some power, she doesn’t have THE POWER. I have to keep reminding myself: Skylar is waiting for Walt to die.

CB: I really think she gave up that sentiment when he gave up the business; she doesn’t hate him with all her being anymore.

JS: If that’s so, that’s a quick change and shows that the writers aren’t all that interested in Skylar. Unless…we’re about to find out a bunch more. Since they go non-linearly about things, they could clue us in. If they just let this go, like she’s all “Whatevs Walt, we’re cool now,” I will be f—— pissed.

CB: I just mean that though she probably hasn’t let him back in their bed, at least the house isn’t a war zone. Not like that amazing dinner scene with Jesse, Walt, and Skylar.

JS: That’s probably my most favorite scene in the whole series, or at least it’s in my top five, and Aaron Paul (Jesse) said the same thing in his AMA at Reddit this week.

CB: And his decisions about the car wash (where to put the different smelling air fresheners) he has to run by her. But it is a fake power, yes. And it’s a different kind of empire: a whole slew of car washes. But that is an example of his transparency with her at least to that degree. Which is a great set up for him blatantly lying to Jesse.

JS: He needs Jesse’s approval. He is so desperate for Jesse to not give up on him.

CB: Yes, Walt wants him to believe him so badly, it almost feels like it’s NOT just a moment of Walt wanting to manipulate Jesse to keep him on his team. It feels like Walt needs Jesse to say yes he believes him so Walt can rewrite his own reality.

JS: I think everything in the previous eight episodes shows that as well. Walt calls Jesse “son,” and he means it.

CB: But it’s different a kind of manipulation, like Walt getting Jesse to come to the conclusion “on his own” to dump his wonderful girlfriend. He seems so much more aware now, so freaked out by Walt and that he’s been associated with this crazy dude. And this is the first time Jesse is hearing about Walt leaving the business.

JS: I love Jesse; I’ve told you he’s the reason why I’ve continued to watch the show. But my husband keeps reminding me: Jesse sucks in real life.

CB: But he’s the moral center! He’s the only non-killer. In a world that is not good, he is the only one to hang our hat on.

JS: My husband says, “Not being willing to be the person who kills someone doesn’t make you the good person.”

CB: There are lots of systems within the world of this Albuquerque. I like how Bobbi Lurie (a poet diagnosed with cancer the same week as Walt, blogging at Berfrois) talks about what the term “breaking bad” means. It means rejecting the normal systems of society and silly waste-of-time niceties, and maybe even our ideas around what’s good and bad. Lurie says: “Walt looks death in the eye. He grows more and more accustomed to it. He handles it. He becomes it. He makes it happen.” Your husband, I believe, is thinking within the confines of normal society. In the system (not our system), in which one has broke bad and therefore defies societal norms, Jesse IS a good person. What being a good person looks like in my privileged writing world (where I don’t need to take care of anyone but myself, and my next phone bill) is way different than what being a good person looks like for someone who is raising a family, etc. There are many worlds within one setting, and each has a subjective code of ethics. In Walt’s former world, being a good person was providing for his kids, being available as a dad and husband. In the meth dealing world, being a good person means not threatening your employees family as a means to power, not murdering children, and generally not totally flipping out and killing everyone.

JS: I get what you’re saying, I do, but I’m still thinking about the difference between breaking bad and being awake (like Lurie’s blog title suggests). I think you’re right, about systems of morality and how they’re shifting. I’m an unabashed relativist who sometimes tries on Truth with a capital T, or Right with a capital R in this case, but I see exactly what you’re saying.

JS: This part of our conversation made me want to revisit this essay by Chuck Klosterman at Grantland, about how Breaking Bad is better than The Sopranos, and Mad Men, and (gasp) The Wire. I am a Wire person, more than a Breaking Bad person, and I remember being annoyed when I read this from Klosterman:

Breaking Bad is the only one built on the uncomfortable premise that there’s an irrefutable difference between what’s right and what’s wrong, and it’s the only one where the characters have real control over how they choose to live.

I think Breaking Bad definitely “broke” towards The Wire. Klosterman continues:

If nothing is totally false, everything is partially true; depending on the perspective and the circumstance, no action is unacceptable. The conditions matter more than the participants. As we drift further and further from its 2008 finale, it increasingly feels like the ultimate takeaway from The Wire was more political than philosophical.

And I thought: what’s the takeaway from Breaking Bad? I mean, it’s crazy manipulative fiction (although my husband keeps telling me: they got these stories from real life, of course people are making Meth in RVs, etc. etc.) And then there’s this quote of Klosterman’s, which I actually agree with and think is really interesting:

This is where Breaking Bad diverges from the other three entities. Breaking Bad is not a situation in which the characters’ morality is static or contradictory or colored by the time frame; instead, it suggests that morality is continually a personal choice. When the show began, that didn’t seem to be the case: It seemed like this was going to be the story of a man (Walter White, portrayed by Bryan Cranston) forced to become a criminal because he was dying of cancer. That’s the elevator pitch. But that’s completely unrelated to what the show has become. The central question on Breaking Bad is this: What makes a man “bad” — his actions, his motives, or his conscious decision to be a bad person? Judging from the trajectory of its first three seasons, Breaking Bad creator Vince Gilligan believes the answer is option No. 3. So what we see in Breaking Bad is a person who started as one type of human and decides to become something different.

One thing I think the show has done well is open up those choices to the other characters as well, to Jesse and Skylar and Hank. But…a set of options is not a choice. Does Jesse have choices: he doesn’t want to kill the kid on the dirt bike (both Walt and Jesse freeze,they don’t make a choice, the guy from Friday Night Lights does), but he helps the kid “disappear.” I think maybe this is the central conflict that the show is going to be: what will Jesse choose to do. When will Jesse have a choice?

CB: I think that the difference between this show and others is the heart of that quote about political vs. philosophical. BB is about the characters making their circumstances, affecting the world even as they are powerless and vulnerable in the face of death (cancer, murderous drug lords, prison or death penalty, etc.). Our subject matter is Walter White and those who he pulls into orbit around him. In The Wire, our subject was the circumstance of the street and all its implications and the people who walked upon it. They could not do much to change their circumstances, unable to do anything but live within their personal and political systems, while decisions were being made about them elsewhere in Washington. When some characters did try to change their circumstances (by adopting, or by opening hamsterdam, by talking to the cops, by trying to stop selling, by trying to get clean), they were ultimately either fired or killed. In contrast, Walter White is going to decide when he goes, most likely. He is the creator of his own circumstances. And perhaps the difference in landscape has a lot to do with that. In New Mexico, those big political decisions (about the drug war specifically) might as well be made on and concerning another planet.

JS: While I think it’s The Wire’s ambitious reach that will always make it my favorite television show, even when it failed or when I failed (Although Chuck Klosterman basically says that white people who say they love The Wire are ridiculous and he basically makes me feel like saying I love The Wire is the same as saying I loved The Help, which…no), I see what you’re saying. But if we’re talking about choices, then we have to be talking about a different show, because there weren’t a lot of choices in The Wire.

CB: Exactly. I totally agree that morality is a personal choice, subjective not objective. And in Breaking Bad, there are more choices even when the characters feel trapped, and we often see them groping about madly for agency (like Skylar in that great scene with Walt about how to protect her kids). Usually, though, it’s within a limited spectrum of choices. Within that spectrum, Jesse is continually leaning towards what we define as good. (To kill or not to kill is a decision that most people are not confronted with; we assume we would choose not to kill.)

CB: With the boy on the bike — I think he did make a choice – to him there was no choice (to kill or not to kill): he WAVED to the boy. If he thought anything, it would be the choice of which lie to tell the kid. And as soon as he saw the gun, he basically threw himself on top of it. But now that the action was done, he made the choice to not get into trouble for it. That’s the difference that the end of the show might present — will Jesse sacrifice himself within that choice? Will he turn himself in/kill himself/try to defeat Walt? Once they made the boy “disappear,” the difference between him and Walt is that he continues to blame himself for not having taken a different course of action. Meanwhile, Walter chocks it up to bad luck, not my problem.

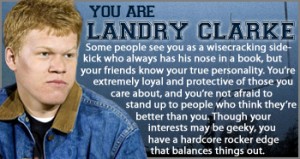

JS: I also just want to add my two cents: it was a brilliant rhetorical choice to have Landry from Friday Night Lights play that character.

CB: Yes! He killed a rapist in Friday Night Lights, and now a child, oye.

JS: It’s like having your favorite character from another novel show up in a totally different novel and kill a kid. They knew we’d recognize him, that we wouldn’t be able to shake his previous character. Brilliant casting. But back to our show.

CB: Skylar has straddled both lines. When questioned, she might say she had no choice, but perhaps she could have jumped full in on either side of the scenario — a partner in crime, or turning him in. That’s a different type of morality — perhaps cheaper and easier, the choice most of us might choose.

JS: And then there’s: what is Hank going to do. I don’t think any of us knows. I was so nervous for Hank, how much he didn’t want Walt to know what he was doing.

CB: Yes. His mouth, jaw so tight.

JS: I really want to see this on the page, as a script, to see what the writers called for and what the actors did.

CB: This episode really doesn’t hold back. It gives us every scene we want. A weaker show would make us wait until later episodes to address this new dynamic.

JS: That’s a criticism of a lot of genre writing as well–that it’s “for the readers” and not for art’s sake. But I feel like, this show knows what we want. Or, rather, it has taught us to want what we want.

CB: But it takes a lot of guts, something that literary fiction does not always have, if I can just throw that generalization out there (for people to argue with if they want): to actually put your characters in a room together, to make them duke it out. To finally fully imagine that show-down moment without over-dramatizing. It’s something that is really hard to do, at least for me as a fiction writer. I’ve lived with my characters for so long, I KNOW them, and yet it is a very scary place to take them: to finally have to face their demons. No matter how well I know them, I have to get to a new place in that knowing to be able to imagine up a believable scene.

CB: “I don’t know who you are. I don’t even know who I’m talking to.” But we do. OH DAMN. This makes me so excited. The show is just so good that it makes me stupid, to be honest.

JS: I know! “Tread lightly” reminds me so much of “I am the one who knocks.”

CB: When Hank brings up his kids. that’s when Walt’s face changes. That’s when he’s honest about how far he’ll go. And concerning the next episode, I wonder if he’ll go straight back and tell Skylar that Hank knows?

JS: Let’s be fiction writers and talk about setting and those great time lapse moments of the sky.

CB: Yes. Let’s talk about the setting. Although maybe that’s too huge! It defines the show. The expanse used to juxtapose the characters tightening or expanding worlds — in the first season I think it represented the freedom that walt’s death sentence let him to be the person he’s always been (if we’re going with that theory, which i like).

JS: The time lapse seems to be in direct contrast to how unrushed the show is at times (though it never seems that way).

CB: The sun and shadows on the landscape are (like that darn pool) a way measure time. (The only way people USED to measure time.) And it reminds us what how tiny they are, these problems, to the indifference of nature and time. And yet they NEED time to make the meth, to build an empire.

JS: Yes, but back to the fiction-y parts. When I read submissions, I’m always interested in the language, tone, characters, more than plot, which would kind of be a no-no in television. And the ending, always the ending. That’s where stories lose their way or become triumphant. And I always want to be gut-punched. I want to gasp, and I’m a slutty gasper, so there’s plenty of ways to make me gasp.

CB: This show must make you gasp a lot!

CB: I’m reading a blog now about all the different handlings of each weapon throughout the series: lily of the valley, ricin, Gus’s boxcutter, the rug that trips Beneke.

JS: It’s interesting if we look at the ricin and think about the rules of theater (or fiction): if you put the gun on the table, it has to go off, right?

CB: Yes. But there are so many guns, they are not usually the point of focus or subject to that rule the way other weapons are.

JS: Walt did buy that gun in the first episode of this season though, and it was a big one. Very out of character. We’ve so rarely seen Walt with a gun.

CB: He buys that tiny gun, when he’s a much more fearful meth cook. Bot times he buys guns are when he’s running for his life. It also reflects his character arc: little gun to big gun.

JS: But it’s the ricin that’s the “gun” for me, not the gun.

CB: Now the ricin the weapon that has to “go off.” And we can’t guess how or who because a “gun” “going off” is challenged and undermined with the lily of the valley. Remember when he uses it like spin the bottle and it points to his next weapon, the flower?

JS: The gun lands on him first!

CB: It lands on him twice! And he’s like, “Nope, I’m not dying like that.” He just defies his own rules of his own little game–a game of chance but alters the rules to fit his needs, playing God. He’s lost so much in that moment. Gus has the power and he wants it. He uses this tool, this weapon that is totally useless against Gus, which then points to the flower–the weapon that indirectly ends up defeating Gus–and he’s like, “Oh yeah I can poison the kid and it looks just like ricin.” Yes, verbatim that’s what went through his head.

JS: But he can’t control everything. I love that so much. That scene has so much artifice all over it, but it’s so captivating.

CB: It opens with an object, the significance of which we’re unsure of. Which is how the show’s structure is often built.

JS: Starting from the end and working towards it.

CB: They used to use that technique for each episode (opening with the EPISODE’S end). Now they are breaking that open and starting with the SERIES’ end. Like Dave Eggers’ You Shall Know Our Velocity.

JS: Or like in any of a number of Alice Munro short stories. It’s fun to think about the connection between fiction and television in terms of how fast we’d flip the pages and how much we might miss if we did that. The show is slowing it down, making us suffer the in-between. If the show was “novelized,” I think no way in hell would I not read it one night. I feel like if this were a book, Gus, Jesse, they would get their own chapters. Maybe even narrated by themselves. Skylar, too, although no doubt she’d still get the short shrift. What if it was narrated by Marie?!?

CB: Her and her poor baby niece in the aftermath of it all! If we were still serializing novels….

JS: For sure. It would be a great graphic novel. Except now that I’m thinking about this, I realize I’d be afraid that James Franco would direct the film adaptation of the novelization.

CB: Now we’re deep in that k-hole.

JS: So while we’ve been trying to read into everything, I’ve been having flashbacks to certain times during graduate school: When we picked apart everything, trying to find the “secret” of it.

CB: But as fiction writers we’re just trying to figure out WHY it works. Close reading is not analyzing to death.

JS: I mostly agree, but one of the best things I ever heard in grad school was this talk that Brian Evenson gave. He was talking about reading The Metamorphosis, and how his professor told him: you know, Gregor Sampsa could’ve just turned into a bug. It doesn’t have to mean something. And I remember thinking: THANK GOD.

CB: But you know Vince Gilligan is this hollywood ego who thinks, There will be whole classes about me! They will never figure out all of my motifs, hahahaha (insert evil villain laugh)…I mean, I’m sure he’s great.

JS: That’s a partially why I think he’s all over the map (and why we are too).

CB: A viewer just has to stick to thinking about these characters as people we care about, and asking the question : why in the world?

JS: Alright, so we’ll have dived deep deep into it and then pulled ourselves back up again to recognize that we have no idea what the hell is going to happen tonight?

CB: That’s your outro.

Carmiel Banasky is a writer and teacher from Portland, Oregon. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Glimmer Train, Guernica, NPR, The Rumpus, Anderbo, TheThe Poetry, and Tottenville Review, among other journals. She earned her BA from the University of Arizona, and her MFA from Hunter College, where she taught Undergraduate Creative Writing. She is the recipient of awards and fellowships from Bread Loaf, Ucross, Spiro Arts, Santa Fe Art Institute, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, Vermont Studio Center, and other foundations. She’s tried her hand at grassroots organizing while living in Mississippi, and studied for a year in London. She now divides her time between Port Townsend, WA (working for Goddard College) and writing residencies across the country.

Jess Stoner is the Managing Editor of American Short Fiction, as well as the author of I Have Blinded Myself Writing This, from Hobart’s Short Flight/Long Drive Books, and You’re Going to Die Jess Wigent, a choose-your-own poetry chapbook about her own death from Fact-Simile. She earned her Ph.D. from the University of Denver, and her fiction, poetry, and essays have been published in The Rumpus, The Collagist, Caketrain, and other handsome journals. She currently lives in Austin, where she helps out in the offices of political folks.