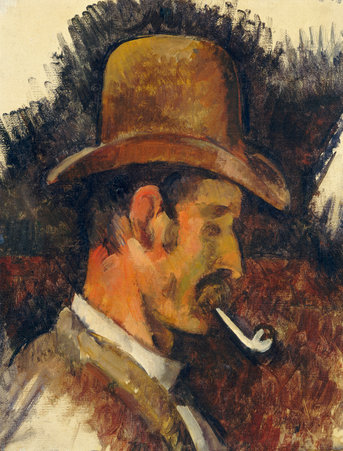

George searched his pockets for change, cluttering the counter with lint and pen caps, a crumpled tissue, pausing to clean his glasses while the tobacconist waited at the open register. It was the tobacconist he cared about, not the neatly lined cigars he had thumbed through moments earlier. George could see the smoke shop from his kitchen window, and last week had watched the tobacconist as he emerged and stood on the street corner in a pouring rain, until his coat was drenched through and rain coursed from his hat. The memory stuck with him—that man, reaching up and touching the brim of his hat to drain the rainwater.

George searched his pockets for change, cluttering the counter with lint and pen caps, a crumpled tissue, pausing to clean his glasses while the tobacconist waited at the open register. It was the tobacconist he cared about, not the neatly lined cigars he had thumbed through moments earlier. George could see the smoke shop from his kitchen window, and last week had watched the tobacconist as he emerged and stood on the street corner in a pouring rain, until his coat was drenched through and rain coursed from his hat. The memory stuck with him—that man, reaching up and touching the brim of his hat to drain the rainwater.

The tobacconist had a face like a mask, then and now—George could not read what the man felt. The counter hid George’s hard-on. He didn’t want to have one. He had no desire for the tobacconist. He worshipped his wife. She was 4’9’’ and called him Hon. She studied Ogham, an ancient British and Irish alphabet and divination system, as a hobby, and worked in the library archives the rest of the time, in a cool, dry, dimly lit room. He wanted to support her by showing interest in her work, so she took him to look at old paper under a microscope and he could see each fiber, weaving the sheet together. She had a gentle way of telling him things that softened the fact that she was smarter than he would ever be. He loved his son, who spent hours after school fashioning a cubby-hole for his wild mice that he fed each evening with a kernel of cracked corn. George built a tree house for his son, and on warm nights his son slept in the tree.

Yet somehow he felt like the tobacconist was an intermediation between a life fully with his family and a life where he could leave them. That’s fiddle faddle, he thought. It was his mother’s word, resurrected from his childhood, from inside the cold, castle-like house where she had spent all her days, reprimanding him and patting his hair. He had not meant to let her in.

He handed his coins to the tobacconist and thought they could run away together, to Europe, to Spain, to a town where all the Ss sounded like a hiss. It was too much to ask that the world allow him this tobacconist. In silence, the tobacconist closed the register and turned away from him, busying himself at the back counter, pinching damp shreds of tobacco onto rolling papers. The nape of his neck was pink. George had a fleeting, terrible image of that long, pink neck on a battlefield, a battle-ax raised above it. He tried to supplant that image with one of his wife in the library, in a red dress—it was possible she might wear a red dress. She was beautiful to him, in a manner of speaking. But the green grass of the battlefield rose up all around her, and then he was again thinking of the man’s neck, up close this time, the lemon smell of the man’s neck. He thought of that brief moment when he had raised his newborn son from his wife’s arms and questioned his paternity, this son who was dark and thin-lipped and looked nothing at all like him. Here he was, on the cusp before the period of mourning and upheaval. For now, he was not a bad man. He had not yet tasted the back of the tobacconist’s neck. He had not yet thrown his wife into contrariety with the tobacconist, or climbed the topgallant mast of a sailboat with the tobacconist, snapper leaping from the water that rushed below them. He had not yet begun to think of his son’s mind as mediocre, or been kicked in the street for being a fairy, a duplicitous fairy, for misreading the look of the man in the bar, not the tobacconist, another man, with nice hands. He had not yet learned the shame of trying to work one’s way back into fatherhood and husbandhood, after you have shown yourself to be a certain type of despicable character. In this moment, at the tobacconist’s counter, the solid sediment of his history was fragile as shale, as easily fragmented. One must learn to keep one’s own counsel. The pavestones leading to life with the tobacconist disappeared. George left the shop quickly. Down in the harbor, a sailboat was lifting its anchor. He would kiss his wife’s neck when he got home, he would slip with her into a bath, he would kiss between her thighs—it was a process of naturalization, making order from the disorder of his fantasy: tobacconist, battlefield, boat, how the wind might have whipped their faces. To have a boy and a wife, he thought, was a gift. What an incredible, incredible gift.

Anna Noyes is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where she received the Henfield Prize for Fiction. Her stories have appeared in Guernica, VICE, A Public Space, and elsewhere. She has served as writer-in-residence at the James Merrill House, and is a 2015 Aspen Words Emerging Writer Fellow. Her short story collection, Goodnight, Beautiful Women, is forthcoming from Grove Atlantic in 2016.