In honor of all of the breathless praise accompanying the release of HBO’s new crime noir series True Detective, The Atlantic is urging readers to revisit two short stories by Nicolas Pizzolatto, the show’s creator. The stories appeared in the magazine ten years ago, when Pizzolatto was an MFA student at the University of Arkansas, and they explore themes that would later mark the HBO series.

In honor of all of the breathless praise accompanying the release of HBO’s new crime noir series True Detective, The Atlantic is urging readers to revisit two short stories by Nicolas Pizzolatto, the show’s creator. The stories appeared in the magazine ten years ago, when Pizzolatto was an MFA student at the University of Arkansas, and they explore themes that would later mark the HBO series.

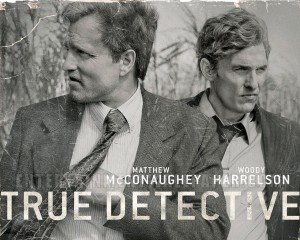

Chief among those is gender and the relationship between men and women. Pizzolatto is a radically masculine writer. The female characters of True Detective serve primarily as foils for the rich inner life of his two lead men: a haunted, philosophically-tinged caricature of the old west lawman played by a sinewy Mathew McConaughey and a thick-ribbed Woody Harrelson, whose character projects stolid family conservatism while he cheats on his wife.

Pizzolatto’s story “Between Here and the Yellow Sea,” published in the November 2004 issue of the The Atlantic, also centers around two men. One is an aging Texas high school football coach (a tragic inversion of Friday Night Lights’ Coach Taylor) whose daughter has run off to California and stars in porn films. The other is the narrator, Bobby Corresi, a few years out of high school, going by Robert now but in no other way older or wiser. He once longingly hoped for romance with the daughter and agrees to help the coach bring her home.

While True Detective snubs the agency of its female characters, in “Between Here,” the daughter, the only real female character, is pure mirage. The magazine’s editors play this up with a journalistic sub-headline below the story’s title: “Coach and I are driving to Los Angeles to kidnap his daughter.”

The show has been criticized for this tendency, notably by Emily Nussbaum of The New Yorker, who wrote that “while the male detectives of ‘True Detective’ are avenging women and children, and bro-bonding over ‘crazy pussy,’ every live woman they meet is paper-thin.”

Plenty of critics jumped to defend the show (perhaps indicating the high perch Nussbaum has in the world of television). Slate’s critic, Willa Paskin, argued that the abhorrent treatment of women is part of the point: “Ignoring women may be the show’s blind spot, but it is also one of its major themes.”

I think wherever you come down on the spectrum, the show’s goals make a lot more sense once you’ve read Pizzolatto’s fiction.

From the very beginning of “Between Here,” the daughter, named Amanda, is purely physical and purely idealized in the Bobby’s mind. The two men are driving and Bobby’s sentences are half-finished, made lazy by the endless road:

“Interstate 10 after midnight, westbound. El Paso now. Coach Duprene says he can drive till morning. Blank asphalt rolls ahead, but I’m seeing Amanda, picturing the way she looked in high school: small-chested in a cheerleading uniform, auburn hair, green eyes, freckles dusting her nose.”

As they drive we get fragments of Bobby’s life: his life at home with only a mother and grandmother (more women foils), his first attempt to be macho (and impress the cheerleaders), which led to a broken jaw at football tryouts and metal stitches in his mandible, his current job that leaves him lonely and finding solace in the poems of Rainer Maria Rilke.

Pizzolatto writes in a high Southern Gothic style chock full of big Rilke-like philosophical statements, and it would get tiresome if not for the visceral details (recalling biology class dissections with Amanda as a lab partner; he writes, “I find refuge from ammonia and formaldehyde in the scent of her hair and neck: shampoo, lotion, sweat.”). It also might get tiresome if not for the main, thriller-esque plot movers: the choloform to make her unconscious; the deprogramming methods the Coach plans to use to kidnap his daughter; and our curiosity about the salacious pornography industry they might discover. The only address they have is for a company called “American XXXtasy.”

It that a cheap move? A ploy to keep us reading? I have no idea what it would feel like to read this story as a woman. I can identify with Bobby’s adolescent longing, his curiosity about the pornography industry, his totally naïve imagination that he could “save” a poor girl from a life of exploitation.

Suggesting some of the narrative tools Pizzolatto will later use when writing television, Bobby tricks a secretary at American XXXtasy into giving him Amanda’s real address. When he eventually finds her, all of his sweaty adolescent memories evaporate in an instant, though not before a quick dip back into puberty. “In the second it takes for the door to swing wide,” Bobby recalls, “I become conscious of my looks, until I remember that I don’t have acne anymore and my haircut is better than it was in high school.”

It turns out Amanda lives with a man — perhaps the biggest caricature of the whole story: “He wears a white tank top, jogging pants, and lots of earrings. His short, glossy hair stands up straight.” — and she’s not interested in being saved. It also turns out that she might be a lot wiser than Bobby, though because we’re trapped in his first-person narration, we only get a sliver. “The world’s a lot bigger than Port Arthur, Texas. Okay? A lot bigger,” she says. “How I make my living isn’t your business, and it sure as hell isn’t that asshole out there’s.” That’s a reference to her father.

We don’t really know why she hates him so much, and her true feelings are kept out of sight. Even in the flesh, Pizzolatto does not quite give her a rich interior life. But we forgive it because we’ve accepted that Bobby will be our guide to this story and that his blind spots will be our own. He can’t understand Amanda so we can’t either.

Because television is by nature a more third-person experience–True Detective features voice over only from the two male leads–it’s harder to forgive, and critics haven’t all been forgiving. The show’s sexuality will be “gratingly familiar to anyone who has ever watched a new cable drama get acclaimed as ‘a dark masterpiece,’” writes Nussbaum at The New Yorker. “The slack-jawed teen prostitutes, the strippers gyrating in the background of police work, the flashes of nudity from the designated put-upon wifey character, and much more nudity from the occasional cameo hussy.”

Nussbaum explains that she is tired of being “a good sport when something smells like macho nonsense.”

It is macho, but I don’t think it’s nonsense. Reading “Between Here and the Yellow Sea” made me understand that Pizzolatto is more conscious of his decisions that it might appear. At the end of the story, Bobby and the coach fail to convince Amanda to come home. As Bobby finishes his feeble pitch to her, he hears a noise outside. It turns out the Coach tried to get inside and the macho boyfriend has beaten him up. “It’s hard not to pity Coach, crumbled on the lawn that way, struggling with a palm over his eye.” It’s a pathetic scene. “Coach sprawls at my feet, holding the chloroform out like some impotent offering. The front door shuts.”

It’s easier to see when Pizzolatto uses naïve, weak male characters that his point is not to eviscerate an interior life from his women. It’s rather to show just how difficult it is for his male characters to understand that life, and how that lack of understanding is tragic and painful and winds up hurting everyone involved.

Earlier in the story, we learn that Bobby grew up only around women, but that he never really learned much about them. “Any coach will tell you that mimicry and repetition are the fundamental learning tools,” he tells us.

“But what could you mimic if you were a boy waking up for seventeen years in rooms choked by perfumes and powders? Say, for instance, every time your clothes got hung on the line, bras and billowing panties flanked them—the mother’s things, skimpy with lace; the grandmother’s wide-bottomed and as big as sails. Say certain things were always on the periphery of your senses: the smell of wet stockings, the reds of lipstick, tampon wrappers. You burned yourself countless times on untended curling irons.”

Perhaps the television format has pushed Pizzolatto into a carnival of machismo. But below the surface you can still see the pain of the curling iron’s burn.

Maurice Chammah is a freelance writer and an assistant editor at American Short Fiction. His journalism, books reviews and essays have appeared in The New York Times, Texas Monthly, The Texas Observer, Guernica, and elsewhere. More of his writing can be found at www.mauricechammah.com