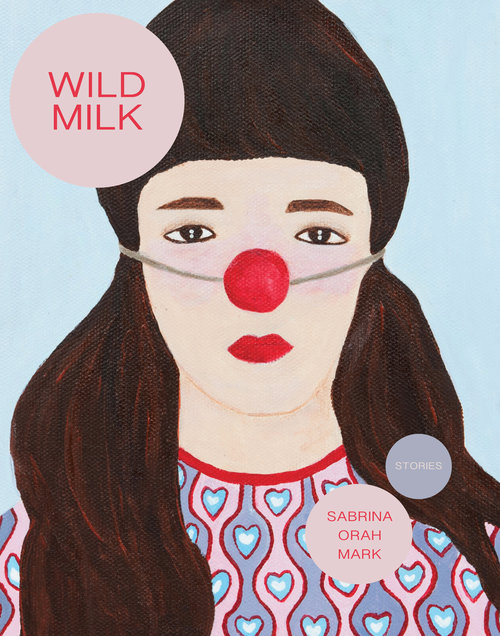

Poet Sabrina Orah Mark is the author of Wild Milk, a collection of surreal short stories that marks her debut in fiction. Wild Milk has been called a “necessary book for our perilous age” by Kirkus and a collection of “tales to wake you up at last” by author Edward Carey. Though short, these stories are deep as the ocean blue. You can drown or swim in them (and enjoy yourself either way). I recently spoke with Orah Mark, who opened up about where some of her wilder ideas come from, how she approaches writing fiction and poetry, and what she’d be doing if she weren’t writing. If you didn’t think she’d own a laundromat, you’d be wrong.

—

Jana Horn: I recently read your book Wild Milk. I think it rocks. And it totally surprised me, which is my favorite feeling as reader. There’s so much metaphor that you don’t always recognize the world where the scene is set. Although the stories maintain a certain semblance of reality, they seem to actually exist in a plane that rests in various heights above and below the tangible world. So I’m curious: in your mind, are we in the real world here, as in: the outrageous is around us right now? Or are these stories imagined—to be taken as their own world with their own logic?

Sabrina Orah Mark: If reality is at the center, then my stories exist one step off by a notch, a letter, a hair, a slant. So “home” becomes “hole,” or poem becomes man. I love this question: “Are we in the real world here?” because it’s a question that asks me to pull these letters I am writing apart and look for dust and bones, a lost glove. It asks me to consider how the imagination hatches the real, and how the real can often slip into the imaginary. The other day my husband asked me, “is that real or a metaphor?” I was talking about a sloth, I think. And I said, “does it matter?” And he goes, “probably not.” I am in love with the moment you cannot tell the sloth from the sloth, or the metaphor from its mother.

JH: This makes me think of Joseph Campbell’s The Power of Myth; he talks about how symbols are just as significant as what they signify, so much that the reality of what is being signified, as you said, “doesn’t matter.” I noticed also in your work how the characters and scenes often seem to be more impressionistic than realistic. I think it’s a really cool technique. By giving the impression of a character, it actually cuts through “reality” to a narrower truth. For instance, the title story takes place in a daycare, which is a familiar setting, but when Miss Birdy, the teacher, opens her mouth, her speech is unraveled, almost nonsensical. It’s funny, but I think it’s more than that—it gives the reader a deeper idea of who she is (more so than with realistic dialogue!) The players in “My Brother Gary Made a Movie & This Is What Happened” are similarly characterized, and made real, by their off-kilter interactions; again, their speech doesn’t make “sense,” yet it’s a great impression of their personalities and inner lives. The reader “gets” them. Could you speak about how you create, develop, and think about character?

SOM: Ah, I love your description of Miss Birdy’s way of speaking as an unraveling. Like a spool of thread. Sometimes a name will start bringing a character into focus, sometimes an utterance. Like the Golem who begins to breathe after the word “truth” is carved into his forehead, my characters live according to language. Like the Golem who dies once the aleph is rubbed from his forehead (changing the word “truth” in Hebrew to “death”), my characters live and die by metaphor. So, if Miss Birdy feels like she’s about to snow, then Miss Birdy will most likely become a blizzard. And this blizzard will be realer than any real blizzard because it’s not only made out of snow and wind, but out of love and fear, too.

SOM: Ah, I love your description of Miss Birdy’s way of speaking as an unraveling. Like a spool of thread. Sometimes a name will start bringing a character into focus, sometimes an utterance. Like the Golem who begins to breathe after the word “truth” is carved into his forehead, my characters live according to language. Like the Golem who dies once the aleph is rubbed from his forehead (changing the word “truth” in Hebrew to “death”), my characters live and die by metaphor. So, if Miss Birdy feels like she’s about to snow, then Miss Birdy will most likely become a blizzard. And this blizzard will be realer than any real blizzard because it’s not only made out of snow and wind, but out of love and fear, too.

JH: Miss Birdy is the realest blizzard! I love it. In regard to the absurd nature of the stories in this collection, I wonder about the chicken and the egg: Does the absurdity come out of the story after you’re writing, like stream of consciousness? Or is it pre-planned? Maybe I’m thinking of the stories “Pool” or “Tweet” that seem to move away from reality as the story unfolds In “Tweet,” the narrator starts by following a Rabbi, which is realistic enough until. . . she follows him inside a goat. She then follows the Rabbi out of the goat (phew) and into an apartment where she is slowly dying, becoming very famous, and married with others who are also following him. When she looks back, she sees endless grass: so much endless grass that she forgets following the Rabbi and starts following “A Person Could Get Lost In This Grass.” Eventually, she unfollows everything. And then “Her Husband” and “Her Babies” start following her. To what extent do these scenarios, so derailed, come out of the actual writing of the scenario? Or do you know where things are going beforehand?

SOM: A few years ago I had a wonderful conversation with the artist Mordechai Rosenstein. Many of his paintings include Hebrew letters, lines from the Torah. He told me when he paints he pays as much attention to the space between the letters as he does to the letters themselves. “Look closely,” he said, “the space between letters are letters too.” I looked closely, and he was right. Gorgeous creatures. They too had shape. They too told stories. Poets often work in these hidden spaces with their ears pressed to the cracks in the walls. As a poet now writing fiction, I pay close attention to those silent spots in a line of prose. Vladimir Nabokov referred to these spots as the nerves or the “subliminal coordinates by means of which a book is plotted.” And there really is no way of knowing those spaces beforehand. They happen as the lines unspool, and the letters form.

JH: You mention a switch from poetry to fiction. Was that organic? Has your process changed as well? What attracted you to writing fiction?

SOM: After I became a mother I could no longer write in ten-hour blocks. So I would stop, and start, and stop again. And the boxes that were once my prose poems began to open. Being interrupted brought to my poems a kind of air that loosened them, thinned them for greater transparency, and the boxes grew, and shed walls, and became paragraphs. And then the paragraphs became stories.

I often think of it it as a boy bursting out his pajamas.

JH: Yes, I think interruptions are so important—they let something else in. As a writer and musician myself, I’m always interested in how different disciplines interact. What you do with fiction, playing with the expectations of format and traditional narrative arc, is not dissimilar to the playful, genre-bending band The Roches, or the ever-clever Jonathan Richman. If there were a soundtrack for this book, what bands would you ask to contribute? What would it sound like?

SOM: I imagine Patti Smith, and my sons, and Roger Miller, and a Hasidic violinist, and long silences, and many mistakes, and starting over.

JH: How delightfully awkward. And brave! This collection of stories actually reminded me of the PT Anderson film Magnolia. The movie goes in and out of the lives of these hyperbolized, complex, larger-than-life characters and ends with (spoiler alert) a rainstorm of frogs. A kid, watching the frogs falling through his window, says: “This is something that happens.” I take a similar kind of stranger-than-fiction perspective from reading your work. It makes me wonder: if you were not an author, what would you be? Would you express these kinds of ideas in another form or do something different altogether?

SOM: Oh, I love this comparison. I’m 100% certain I would own and operate a laundromat. A beautiful, glowing laundromat. Open all night. I might even name it “Nowhere Suds.”

JH: It sounds like you’ve already thought this through. You had me at “100%.” Let me know if you’re looking for an investor . . .

SOM: Ah, I am. We can build an empire out of rinsing, and spinning, and tumbling dry low.

JH: Which books have been the most important to you? Besides other authors and books, what other artists and works of art are you inspired by?

SOM: Ah there are so many: Reginald McKnight, Bruno Schulz, Edward Carey, Amber Dermont, Elizabeth McCracken, Yusef Komunyakaa, Kate Zambreno, Kristen Iskandrian, Christine Schutt, Lydia Davis, Mary Ruefle, Danny Khlalastchi, Samuel Beckett, Donald Barthelme, Leonora Carrington, Franz Kafka, Gertrude Stein, Adrienne Kennedy, Anne Boyer, Oni Buchanan, Lucie Brock-Broido . . .

One of my favorite things on earth is Magritte’s “Healer.” He has a birdcage for a head and a chest, and the cage is open so the birds can fly in and fly out. A few months ago my friend Amy said to me, “I hope you’re not afraid of mice.” We were in her car. She opened up the glove box and inside was a nest of fur, and paper, and string. A mouse nest. A mechanic told her eventually the mice will nibble the guts of her car, but she won’t disturb the nest. I love Amy like I love “The Healer.” Both, like a poem, protect our gentlest ones. And tell a story about kindness and protection and ruin.

JH: What’s the best piece of advice you’ve been given?

SOM: What doesn’t kill you makes you funnier.

Sabrina Orah Mark grew up in Brooklyn, New York. She is the author of the book-length poetry collections The Babies (2004), winner of the Saturnalia Book Prize chosen by Jane Miller, and Tsim Tsum (2009), as well as the chapbook Walter B.’s Extraordinary Cousin Arrives for a Visit & Other Tales from Woodland Editions. Her collection of stories, Wild Milk, was published my Dorothy in 2018. Mark’s awards include a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, a Sustainable Arts Foundation Award, and a fellowship from the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Her poetry and stories most recently appear in American Short Fiction, Bennington Review, Tin House (Open Bar), The Collagist, jubilat, The Believer, and have been anthologies in Best American Poetry 2007, Legitimate Dangers: American Poets of the New Century (2006), and My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me: Forty New Fairy Tales (2010). She has taught at Agnes School College, the University of Georgia, Rutgers University, the University of Iowa, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Goldwater Hospital, and throughout the New York City and Iowa Public School System. She lives in Athens, Georgia with her husband, Reginald McKnight, and their two sons.

Jana Horn is a fiction writer and musician from Glen Rose, Texas. She received her BA in Creative Writing from St. Edward’s University and has spent the past decade recording albums, writing short stories, and touring the U.S. and abroad solo and as a member of Knife in the Water. Her solo album “Optimism” is due later this year. She now performs as American Friend with multi-instrumentalist Adam Jones. She is an assistant editor at American Short Fiction.