Bret Anthony Johnston has the distinction of being among the few writers occupying that slim but coveted slice of the Venn diagram: creative writing directors (Johnston is at the helm at Harvard) who have toured the country on a professional skateboarding team. Find a great discussion on this over at McSweeney’s.

Bret Anthony Johnston has the distinction of being among the few writers occupying that slim but coveted slice of the Venn diagram: creative writing directors (Johnston is at the helm at Harvard) who have toured the country on a professional skateboarding team. Find a great discussion on this over at McSweeney’s.

His latest work, Remember Me Like This, is a quiet and rich novel centered around a teenage boy named Justin who is returned to his family four years after his kidnapping. The story cycles through the perspectives of his parents, younger brother, and grandfather. Their experiences stitch together a gorgeous portrait of South Texas, pulling together lives spent at skate parks, marine labs, and pawn shops—lives bound by the looming unknowns of Justin’s captivity.

Johnston’s will speak about and read from the novel this Tuesday, September 9, at BookPeople in Austin. The event begins at 7 p.m.

He was kind enough to talk with us about his writing process, the virtues of bulletin boards, and his experiences with a clown convention in Houston.

AB: From the opening of the book, I was struck by the specific quality of light, heat, shadows, and storms of the Gulf. What effect did the setting have on the pace and direction of the novel?

BAJ: Thanks for these kind words. I wanted the weather to impose itself on the characters; in fact, I wanted it to become something of a character. Texas heat tends to do that. On some level, I suppose I wanted it to be inescapable and oppressive, a kind of external manifestation of the pressure the family is facing internally. Chekhov famously advised writers to make sad stories very cold, so I wanted to see what effect it would have to saturate a story in drenching heat.

AB: One of my favorite aspects of Remember Me Like This is how it parts ways with expectations I had about kidnapping stories. It resists graphic scenes between Justin and his kidnapper and focuses instead on the family’s experience. Were you surprised by anything that approach led you to while writing the novel?

BAJ: Again, I’m grateful for the way you’ve read the book. I really am. Most of what happens in the book was a complete surprise to me, and each of the surprises felt like a gift and revelation. As a writer, I crave surprise. I require the story to move in unexpected directions and for the characters to lead, rather than follow, me. I could list countless surprises, but for now I’ll just focus on Justin. I always expected him to have a POV in the book. Somewhere on my computer there are a couple of chapters written from his perspective, and in my memory, they’re pretty good. But the deeper I got into the narrative and the more I came to empathize with him, I understood that he wasn’t ready to tell his story. And, in truth, he may never choose to tell it. I don’t know. But I knew he wasn’t ready to disclose more than he does now, so to force his POV into the novel would have been an egregious violation of his privacy. It would have felt obscene and opportunistic, and if his family was vowing to respect his privacy and process, then I took that vow too.

AB: Justin feels like the nucleus of the story. With his return home, it’s as if he has gone from a kind of “ghost nucleus,” a gravity that can’t be pinpointed, into something material. We circle him through the point of view of his family, receiving alternating views of who Justin is and what the traumatic experience means. This is a roundabout way of asking about the architecture of the novel. Could you talk about how you envisioned it and how it evolved?

BAJ: That’s a really apt way to describe his role in the novel, and I’m glad that it worked. The first draft of the book was 600 manuscript pages and the second was 350. I cut out 250 pages and didn’t even feel it because the writing was so abysmal. That said, I needed to write those many bad pages to find the ones that were sturdy enough to lead me into the subsequent drafts.

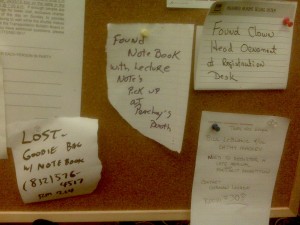

In the most practical sense, I tried different tactics for keeping track of everything that happened. What worked best was getting an enormous bulletin board and listing what happens and shows up in each chapter in color-coded ink. Laura was, I think, blue, and Eric was green, etc. The approach allowed me to see the book holistically and keep a running inventory of what the readers and characters knew at a given time. I would look at the board and think, “We haven’t seen Alice in a while. Bring her back.” Or: “Where did the postcard go?” It wasn’t a matter of forcing the plot or certain artifacts back into the narrative, I never felt as though I were engineering an artificial encounter or observation, but rather, the board was a way of reminding myself what was going on in the characters’ world as opposed to mine.

AB: Alice, a rehabilitating dolphin, is a perfectly strange addition to the cast of characters. Could you tell us a bit about your experiences with dolphins?

BAJ: In a certain way, the story started with Alice. A little over twenty years ago, I volunteered to help rehabilitate a dolphin in almost exactly the same way Laura does. The difference is that all of my shifts were in the afternoon because I could never volunteer for the overnight shifts. The rescue coordinator told me those were the hardest slots to fill, and yet there was never an open shift. For two decades, I’d wondered who was taking all of those notoriously difficult shifts, and little by little, year by year, the character started to crystallize. Obviously, I thought of someone with insomnia, but then I started to think that maybe she was also looking for privacy, for some kind of anonymity. So I started thinking of her as a married woman who was signing up for her shifts under her maiden name. But what was keeping her up continued to nag me. After another few years, I remembered that someone had brought in a beach ball for my dolphin to play with, and I thought that my character was the kind of woman who would do such a thing. Problem was, I don’t think of a beach ball as the kind of thing that adults have. I think of them as toys for kids, and I’d never once thought of her as being a mother. That’s when I knew there was a book to be written, a narrative that would sustain my curiosity and attention: I hadn’t thought of her as having a son because he was missing, and his absence was what was stealing her sleep every night. I understood that she was bringing in the beach ball as a way to save the dolphin because she felt as though she’d failed to save her son. The clincher was when it occurred to me that it’s rarely the parent who blows up the beach ball. It’s the child who blows it up, so she was bringing in a beach ball full of her missing son’s breath. I think I started writing immediately. Eventually I changed the beach ball to an inflatable alligator because I’m forever trying to get more animals into my fiction, even fake ones.

AB: Did you ever write from Alice’s point of view?

BAJ: No. I don’t yet feel up to that challenge. There are writers who have done this beautifully—William Maxwell and Paul Bowles come to mind—but I’m not one of them.

AB: Shrimporee is a strange and wonderful slice of the story. It’s also a real event that’s documented by some amazing YouTube clips of shrimp cooking, motorbike parades, and Elvis impersonators. What secrets can you impart about Shrimporee?

BAJ: Two words: Outhouse races!

AB: Your collection Corpus Christi and Remember Me Like This both explore the region where you grew up. What do you find most interesting about writing in Texas, and do you expect your focus to stay there?

BAJ: The longer I’m away from the state, the more interested in it I become. I see no signs of my curiosity waning, and I’m grateful that the stories keep offering themselves. I feel no compunction whatsoever about it. I’m close to finishing another collection of stories and I’ve got a couple of ideas for two novels, all of which take place in Texas. “Paradeability,” a story that I was lucky enough to publish in American Short Fiction, was the result of a skateboarding trip that I’d taken with a buddy to Houston. We’d spent the day skating, and when I limped into the hotel, the lobby was crowded with about two hundred clowns.They were there for the annual convention. I remember my shin was bleeding and the clowns were surprisingly—staggeringly—unfriendly, but I knew I’d been given a gift. I snuck into their panel discussions and contests, snapped pictures, and just barely talked myself out of stealing a notebook of notes that one of the mean old clowns had left behind. Immersed myself in a story that could only happen in Texas. It’s what I’ve been doing for as long as I can remember.

BAJ: The longer I’m away from the state, the more interested in it I become. I see no signs of my curiosity waning, and I’m grateful that the stories keep offering themselves. I feel no compunction whatsoever about it. I’m close to finishing another collection of stories and I’ve got a couple of ideas for two novels, all of which take place in Texas. “Paradeability,” a story that I was lucky enough to publish in American Short Fiction, was the result of a skateboarding trip that I’d taken with a buddy to Houston. We’d spent the day skating, and when I limped into the hotel, the lobby was crowded with about two hundred clowns.They were there for the annual convention. I remember my shin was bleeding and the clowns were surprisingly—staggeringly—unfriendly, but I knew I’d been given a gift. I snuck into their panel discussions and contests, snapped pictures, and just barely talked myself out of stealing a notebook of notes that one of the mean old clowns had left behind. Immersed myself in a story that could only happen in Texas. It’s what I’ve been doing for as long as I can remember.

Bret Anthony Johnston is the author of best-selling novel Remember Me Like This, a Barnes & Noble Discover pick and a New York Times Book Review’s Editor’s Choice. He is also the author of multi-award winning Corpus Christi: Stories and the editor of Naming the World: And Other Exercises for the Creative Writer. His work appears in American Short Fiction, Virginia Quarterly Review, Esquire, The Atlantic Monthly, The Paris Review, and The Best American Short Stories. He has received awards from the Texas Institute of Letters, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Pushcart Prizes, the National Book Foundation, and elsewhere. He is the Paul and Catherine Buttenweiser Director of Creative Writing at Harvard University.

Andrew Bales is the Digital Editor at American Short Fiction.

“Paradeability,” Johnston’s story about the clown convention in Houston, is in the Fall 2011 issue of American Short Fiction. This fantastic back issue is available for purchase in our store. Please specify Issue 53.