With two chapbooks, a short story collection and a novella in flash under his belt, Matt Bell has been quietly turning heads for years, accumulating acolytes and critical acclaim with his heady brand of visionary lyrical surrealism. Bell, along with the celebrated likes of Karen Russell, Aimee Bender, and Téa Obreht, is among a generation of young writers working far outside the bounds of mimesis to create a new kind of mythology more fully equipped to describe an increasingly absurd and disconcerting reality. Bell’s anxiously awaited debut novel, In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods, out this month from Soho, is the haunting and hypnotic fever-dream of a newlywed husband whose plan to forge a family in this remote landscape is complicated by forces lurking beyond or beneath each of the elemental surfaces named in its appropriately epic title, including a giant squid, a pissed off bear, and the nearly bottomless labyrinthine grief of his wife, whose power to sing whole worlds into being may not be enough to give her husband what he wants. Matt generously took time out from a brief break on his current tour in support of the novel to talk to us about it via email.

With two chapbooks, a short story collection and a novella in flash under his belt, Matt Bell has been quietly turning heads for years, accumulating acolytes and critical acclaim with his heady brand of visionary lyrical surrealism. Bell, along with the celebrated likes of Karen Russell, Aimee Bender, and Téa Obreht, is among a generation of young writers working far outside the bounds of mimesis to create a new kind of mythology more fully equipped to describe an increasingly absurd and disconcerting reality. Bell’s anxiously awaited debut novel, In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods, out this month from Soho, is the haunting and hypnotic fever-dream of a newlywed husband whose plan to forge a family in this remote landscape is complicated by forces lurking beyond or beneath each of the elemental surfaces named in its appropriately epic title, including a giant squid, a pissed off bear, and the nearly bottomless labyrinthine grief of his wife, whose power to sing whole worlds into being may not be enough to give her husband what he wants. Matt generously took time out from a brief break on his current tour in support of the novel to talk to us about it via email.

AT: In the same way we’re often unable to talk coherently about our dreams with other people, I’ve found it difficult to talk about this book with anyone who hasn’t also read it and experienced the myriad happenings in and around and under that titular house upon the dirt between the lake and the woods for themselves. I’m wondering if that was true for you while you were writing it, and what it’s like now to take this story out into the world and talk about it with people who might not be familiar with your work, or with fabulist fiction in general.

MB: In the House really can be a hard book to talk about, right? It doesn’t synopsize particularly well, and it resists other kinds of reductions too, which I think I find reasonably reassuring. It seems like many of my favorite books resist similar attempts, and so I’m reasonably happy that mine does too. (Which isn’t to say I haven’t found a way to describe it when asked, only that what I describe might not be completely accurate.) I held off for a long time from telling anyone about the book: Most of the first two years I was writing it, I was completely secretive about it, and it wasn’t until I was nearly finished that I shared anything about the book with anyone else. I can still remember the first conversations with my initial readers, who started to repeat some of the book’s contents back to me—the giant squid, the ruined bear, the second moon and the deep house, and especially the children, the fingerling and the foundling—which brought home what a weird book I’d written. I’d gotten used to these elements, of course, having spent so much time with them, and so it’s always interesting to talk to people who are just encountering them for the first time. Out in the world, I try to offer a point of entry into the book by describing it as a myth about marriage and about the desire to be a parent, which seems like a fair enough way of describing its broadest aims in a way that hopefully grants people access to it. In different cities I’ve visited during my tour, I’ve been glad to see it received in many different ways, at least as evidenced by questions during Q&As and signings: I’ve talked about fairy tales in Lansing, about the acoustics of the language in Kalamazoo, about myths and dreams in San Francisco, about gender politics in Seattle, about religion in Denver. I’ve always hoped the book would be a space for readers to have an experience all their own, and I’m thrilled to see all the various ways they’re engaging the story.

AT: As with all of your work, the novel is written in a deeply poetic vernacular that is peculiarly yours. I’ve read several sections aloud to my cat over the last few days and I swear to you she rubs her face along the corners of the cover and purrs her approval. It’s part of what makes a book like this possible, I think, the rhythm of these sentences, the reader rendered helpless in the face of this music. How important are the sonic qualities of your narrator’s language? Do you enjoy reading your work in front of people? Is the performance element something you spend much time focusing on?

MB: The acoustic qualities of language are always very important to me, and I spend a lot of time reading my work aloud during drafting and during rewriting. It’s one of the ways that I know how to unify a book—to make it all of a piece can mean to make it all of one singular voice—but I think that there’s a more important gain in writing prose like this: Even if a reader never hears the words aloud, I think the innate acoustics of the words have a bodily effect, and that those sounds carry emotional content that supports or subverts the intellectual or plot content of the sentences. It’s such a powerful tool that I can’t imagine trying to write without it: Why would I ever want the prose to be only informational, when it can contain both information and music? Thanks for asking about reading in front of people too: I really do enjoy the chance to read to an audience, and I continue to try to get better at making my writing fit that task, to do my best to deliver a performance worthy of their time and attention.

AT: Thematically, In The House Upon The Dirt Between The Lake And The Woods is very much in line with ideas you started exploring with “Walker, Wallace, Warren,” which originally appeared in American Short Fiction, and all the pieces in its attendant collection, (or novella, or whatever) the apocalyptic parenting guide that is Cataclysm Baby, which felt something like a breakthrough to me, somehow even more weighty and elemental than the meditations on death and disappearing that comprised How They Were Found, so I was thrilled that you continued exploring them here. The stakes seem even higher, more personal and emotionally fever-pitched. Have you said everything you have to say on the subject, or can we expect more of these venereal horror stories, archetypal marriage myths and deconstructions of the family unit? Also, and I’m only partially kidding here, do you think your work serves on some level as a kind of therapy for you? As a reader, there is something incredibly cathartic about it, like a particularly illuminating dream, to return to that lazy analogy, which lays bare all of our unconscious anxieties and forces recognition of, if not a direct confrontation with, very basic and primal fears. One suspects a Jungian psychologist would have a field day with this book.

AT: Thematically, In The House Upon The Dirt Between The Lake And The Woods is very much in line with ideas you started exploring with “Walker, Wallace, Warren,” which originally appeared in American Short Fiction, and all the pieces in its attendant collection, (or novella, or whatever) the apocalyptic parenting guide that is Cataclysm Baby, which felt something like a breakthrough to me, somehow even more weighty and elemental than the meditations on death and disappearing that comprised How They Were Found, so I was thrilled that you continued exploring them here. The stakes seem even higher, more personal and emotionally fever-pitched. Have you said everything you have to say on the subject, or can we expect more of these venereal horror stories, archetypal marriage myths and deconstructions of the family unit? Also, and I’m only partially kidding here, do you think your work serves on some level as a kind of therapy for you? As a reader, there is something incredibly cathartic about it, like a particularly illuminating dream, to return to that lazy analogy, which lays bare all of our unconscious anxieties and forces recognition of, if not a direct confrontation with, very basic and primal fears. One suspects a Jungian psychologist would have a field day with this book.

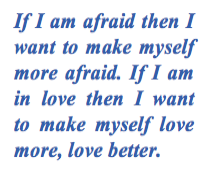

MB: There are a few ways to talk about the books thematically—and thank you for your own kind readings—but I think that in some ways it’s best to stay a little distant from naming them too closely, at least as the writer, both to avoid over-determining the reaction of readers, and to keep from knowing too much about what I’m doing, which might get in the way of organically producing the next thing. The writer is both the first reader of the book and the only person who can never really experience the book as a real reader will, and that paradox can be generative of future work if it isn’t mucked with too much. That said, I’m a fairly obsessive person, and my greatest obsessions are going to keep recurring in different ways. My family and my marriage are both at the center of my life, and it’s no surprise that they’ve featured at the center of my work. The new book I’m working on is in a different mode, and the family isn’t at the center of the book’s plot, but I think some of these concerns are still being continued there, in less fantastical ways. It’s not the worst thing. The family and the marriage are maybe the closest we have to universal experiences, even given all the variations in childhoods and marriages and so on, and in worlds as weird as mine, they perhaps serve as touchstones of shared experience, portals where readers can enter the book through their own emotions. As for the idea of writing as therapy: The work definitely does a variety of things that are useful and helpful for me, but I don’t think of writing as therapeutic. The work isn’t necessarily about getting over anything, or getting past it, or getting better, whatever that would mean. The work is about getting more. More of my emotions, more of my life. More feeling, more thought. Not to escape an obsession but to build a world in which an obsession might more fully live. If I am afraid then I want to make myself more afraid. If I am in love then I want to make myself love more, love better. Writing is one of the ways to push those emotions, to get inside them and try to make them larger or more visible. It’s turning into yourself instead of turning away.

AT: There’s also something thrillingly confrontational here about your complete rejection of realism and standard literary tropes. While the relationships and emotional core are always wholly recognizable, almost nothing else in this world follows natural laws. This remains an affront to some academics still tied to century-old notions about the nature of art and the function of the novel in particular. Obviously, you’re not alone in flouting stagnant literary forms. The last few years have brought a slew of prominent works by young writers owing more to Barth and Borges than Steinbeck or Updike or Roth, but I think you are certainly among the most daring and the most rebellious. Do you see yourself that way? Without naming names, has anyone ever tried to make you a more conventional stylist or to steer you into a more populist or strictly mimetic mold? Did anyone ever try to turn you into Franzen, to pick an easy target?

MB: The only person who ever tried to steer me toward a more purely realist world was myself: There was a period when I was first seriously writing where I was mimicking what I thought literary fiction was supposed to be, and I produced a lot of stories based on my readings of Raymond Carver and Amy Hempel and Denis Johnson and so on. (Although all of those writers have their own kinds of magic, of course, especially Johnson, whose books spoke to me louder than anyone else’s for a very long time, surely in part because of the liminal spaces in them, the way a drive-in movie theater can be both a theater and a cemetery full of torn sky and descending angels at the same time.) Those writers are all still writers I love and reread and teach, but they’re not exactly the kind of writer I was going to become, obviously. At some point—let’s say 2008 or so, right before I went to grad school—I started letting the fantastic and the mythic and the fairy tale back into my work, alongside urges leftover from being a voracious sci-fi and fantasy reader, and then my work started to come alive, in no small part because I was, at last, being myself upon the page instead of who I thought I was supposed to be. But even that going away from myself was useful, because it taught me other tools I might not have learned otherwise. There are reasons to write the wrong stories that are just as good as the reasons we compose the right ones.

AT: The epigraphs to How They Were Found and Cataclysm Baby are from Mark Danielewski’s infamous House of Leaves and Cormac McCarthy’s apocalyptic masterpiece The Road, respectively. It seems to me those two works also offer nearly perfect points of triangulation for your aesthetic, with the formal rebelliousness of House of Leaves and the mythic, Old Testament language of The Road, (whose nameless man and boy are perhaps echoed in In The House Upon The Dirt’s husband, wife and child) Can you talk a little bit about your influences in terms of works that have left a deep enough mark on you that they made a measurable impact on the page?

MB: I haven’t read House of Leaves in full again since I first read it, maybe ten years ago, but it left an impression that now seems to fit the book well: I don’t remember much of it in particular, but I remember the experience of it vividly, if that makes sense, and the way that it was both formally unlike anything I’d ever seen and also one of the most terrifying books I’d yet read. The Road is one of my favorite McCarthy books, and a touchstone I go back to often both as a text and as an experience. There are lots of other influences on my work, writers like Brian Evenson, Laird Hunt, Aimee Bender, Rikki Ducornet, George Saunders, Christine Schutt, Denis Johnson, David Ohle, Stanley Crawford, and on and on. But I think influence is deeper than a list of the most obvious names: I worked on this book for about three years, and in those three years I read three hundred books, plus countless issues of literary magazines and so on, and every single thing I read surely made some difference in the book In the House became. We write out of our imagination, but our imagination requires fuel, and the only fuel we can feed it is our life experience and our art experience. And in the same way that this book is probably particular to the time in my life I wrote it—I couldn’t have written it ten years ago, and I won’t want to write it again ten years from now—it’s also particular to the reading and listening and watching I was doing in this time. More and more I’ve come to recognize that claiming influence isn’t about making a list of favorite writers, but about an acknowledgment of effect, a recognition of what other artists’ have made in you by their own good works.

AT: The buzz about this book has been building for months, and now that it’s here and being received with predictably rapturous reviews, a lot more people are starting to know who you are. Does a measure of literary fame sit well with Matt Bell? Are you comfortable being the voice of new wave fabulism? Do you think genre distinctions are even relevant outside of market considerations?

MB: Genre distinctions definitely have their uses, and sometimes are even helpful as framing the work I intend to do. But in the end they tend to be more fluid than certain. My work that is overtly mythic or fabulist, like In the House, tends to also be grounded in a concrete world in a way that myths are not—and at the same time, the more obviously realist work I’ve been writing recently still contains a measure of myth, certain techniques drawn from fairy tales, ways to incorporate the everyday magic of being alive. For me, genre is always more interesting as a spectrum, and I look forward to continuing to slide in different directions with different books. As far as literary fame: I’m incredibly grateful for the championing so many other writers have done on behalf of this book, and the way that booksellers and reviewers have gotten behind it to get it into the hands of more readers. But I don’t think I’d claim myself as the new voice of anything or anyone except myself, and if anything results from any perceived sense of a bigger audience, I hope it’s that my standards for my own work will continue to rise: I am always looking for ways to push myself harder, to take the work farther, and perhaps knowing there is a bigger audience looking in my direction is one of those ways. In art, as in the rest of life, it’s generative of goodness to be held accountable.

AT: Having moved in stages from traditional length short stories, to a novella in flash and on to this novel length work, do you see yourself returning to short fiction any time in the near future?

MB: Absolutely. Really, the pace of book publishing makes these things look more linear than they are: I started drafting Cataclysm Baby before How They Were Found was finished, and I worked on In the House throughout the period both books were going through the editorial process at their presses, and as they were being released into the world. I think Soho acquired In the House the week before Cataclysm Baby came out, and so on. So the books were written in order, but they were really all of a similar period, and I was often moving back and forth between forms. There’s always a certain amount of overlap—for instance, I’ve been working on my next novel for well over a year now, even as I occasionally took breaks to do edits on In the House—and that overlap includes some move between forms as well. Unless something changes, the next book will be the new novel, and then a collection after that. I’ve written a good number of stories since How They Were Found was finished (I think the last story in that book was written in 2009), and I’m looking forward to writing more: As much as I love the novel, I’m looking forward to the chance to more quickly move through forms and voices that story writing allows, and the ways that new short fictions might set up new longer projects. It wasn’t until I’d written a book or two that I realized how each finished work could be both its own thing and also generative of what would come next, and I think stories are for me the perfect engines of this kind of discovery.

#######

Matt Bell will read from In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods this Saturday, July 13th, at 4 p.m. at BookPeople in Austin, Texas. We hope to see you there.

Aaron Teel is the author of Shampoo Horns (Rose Metal Press, 2012). His short fiction has appeared on Tin House, Smokelong Quarterly, Monkeybicycle, and Matter Press, among others. Find out more at www.aaron-teel.com