While the current crisis in Egypt makes the front pages of our papers on an almost-daily basis, the country’s complex, hopeful, and conflicted revolutionary history has also been written in its fiction. This week at ASF, we’re featuring two essays that explore the political climate and events that shaped region – through the filter of literature.

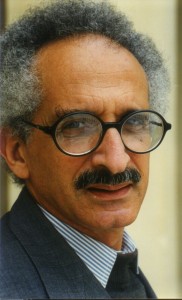

The Egyptian writer Sonallah Ibrahim has been getting much attention in the U.S. these days. In March, his 1966 novel, That Smell, was published in a new translation by Robyn Creswell, poetry editor of the Paris Review and professor of Comparative Literature at Brown University. The book was reviewed in the New York Review of Books, The Daily Beast, and The Coffin Factory, to name a few, and it was featured on The New Yorker’s website, where Creswell calls Ibrahim “Egypt’s Oracular Novelist.”

The Egyptian writer Sonallah Ibrahim has been getting much attention in the U.S. these days. In March, his 1966 novel, That Smell, was published in a new translation by Robyn Creswell, poetry editor of the Paris Review and professor of Comparative Literature at Brown University. The book was reviewed in the New York Review of Books, The Daily Beast, and The Coffin Factory, to name a few, and it was featured on The New Yorker’s website, where Creswell calls Ibrahim “Egypt’s Oracular Novelist.”

I first came across Ibrahim when I was living in Cairo in 2011. My partner and I had hired a tutor to study Egyptian short fiction. Our Arabic, while functional, is by no means solid enough to embark on the task of reading an entire novel, but short stories were manageable. One evening, over cups of loose tea, we stammered through the opening of one of Ibrahim’s more recent novels, Stealth. I was instantly charmed by the narrator’s innocent tone, by the images of Egypt in the late 1940s—of pocket watches and tramcars with wooden benches and political dissidents marked by their western-style suits and tilted tarbouches—and wanted to read as much Ibrahim as possible.

To my dismay, however, I found that very few of his writings (four of twelve novels, an essay, and a handful of short stories) were translated into English. (There are, surprisingly, more of them translated into French.)

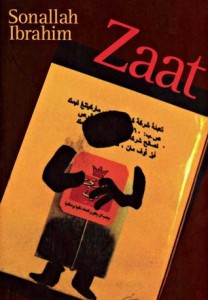

But, luckily, Zaat is translated (beautifully by Anthony Calderbank, translator and Country Director of the British Council in South Sudan) into English. Set in Heliopolis, a suburb northwest of downtown Cairo, the novel follows the lives of a woman named Zaat and her husband, Abdel Maguid. The book takes place over about fifteen years, spanning the rule of three Egyptian Presidents: Anti-Colonialist Gamal Abdel Nasser in the late 1960’s, Western-loving Anwar Sadat in the 1970s, and crooked Hosni Mubarak in the 1980’s. Ibrahim presents to readers an Egypt steeped in consumerism, intellectual and spiritual emptiness, and corrupt government bureaucracy. Though obviously frustrated, his characters do not express political dissent. Instead, they strive to change their lives in the only ways they know how: through material gain and a visible (though empty) religiosity. For Ibrahim, this superficiality is a direct result of oppressive regimes, which he illuminates through his ironic tone and removed narration, as well as the novel’s unique structure.

But, luckily, Zaat is translated (beautifully by Anthony Calderbank, translator and Country Director of the British Council in South Sudan) into English. Set in Heliopolis, a suburb northwest of downtown Cairo, the novel follows the lives of a woman named Zaat and her husband, Abdel Maguid. The book takes place over about fifteen years, spanning the rule of three Egyptian Presidents: Anti-Colonialist Gamal Abdel Nasser in the late 1960’s, Western-loving Anwar Sadat in the 1970s, and crooked Hosni Mubarak in the 1980’s. Ibrahim presents to readers an Egypt steeped in consumerism, intellectual and spiritual emptiness, and corrupt government bureaucracy. Though obviously frustrated, his characters do not express political dissent. Instead, they strive to change their lives in the only ways they know how: through material gain and a visible (though empty) religiosity. For Ibrahim, this superficiality is a direct result of oppressive regimes, which he illuminates through his ironic tone and removed narration, as well as the novel’s unique structure.

As a character, Zaat is quite boring. She’s average looking, middle class, a little bit thick, and completely preoccupied with social status. She has few friends and very little to talk about. In fact, one of her daily struggles is trying to collect interesting stories (or, as the narrator calls it, “transition material”) so that she can gossip with her coworkers (“the machines”) at a newspaper office.

Ibrahim’s narrator, however, is quick, sarcastic, and laugh-out-loud hilarious. While the novel could begin with Zaat’s birth, the opening quickly points out that such details “would certainly constitute nothing but a waste of time for the reader and writer alike. Time which could be better spent in front of the television, for example.” Recognizing that Zaat’s personality and desires are the norm in Egyptian society, the narrator is critical with a tongue-and-cheek tone yet does not come off as self-righteous or overly-elite. There is a George Saunders-like compassion to the irony that connects the characters to the reader (Zaat and her family could be part of your own) making the superficial, consumer-obsessed culture seem even more tragic.

Ibrahim suggests that material preoccupations are not a result of a lazy, vapid culture, but that they have trickled down from colonialism and globalization, which, in turn, have bred governmental corruption, bureaucracies, and a misplaced attempt to appeal to the West. We see this in Zaat’s community, in the way she and her family speak, in what she and her neighbors buy, in the advertisements around them. While they are dating, Abdel Maguid tries to impress Zaat with his worldliness, responding to her requests not in Arabic but in accented English: “oov koors.” Later, readers are introduced to “their miracle child,” a boy who could “say apple and orange in English completely fluently, though he was incapable of pronouncing them in Arabic.” Similarly, while wandering the streets of his neighborhood, which is near the airport, one afternoon, Abdel Maguid notices a billboard:

Keep Heliopolis clean, it is the first thing the tourist sees!

In these quick, funny details, readers see how betterment of the country (education, less-pollution), is not for the sake of Egypt and Egyptians, but for outsiders. Ibrahim is suggesting that colonialism did not die with the end of British Occupation in 1953, but that it lives on via tourism and globalization.

We also see this emptiness and appeal to the West in real headlines, clippings, and advertisements from Egyptian newspapers. Each chapter alternates between Zaat’s story and these news segments, which are presented in various sized fonts and, at times, are bordered by thick, black boxes. “If you find this arrangement mildly inconvenient,” Anthony Calderbank writes in the introduction, “try to imagine an Egyptian’s reaction, as he peruses those same advertisements in his language, to all the foreign words and alien product brand names he finds masquerading in the Arabic script.”

Early on, one headline reads:

An economist: American Aid is nothing more than loans to Egyptian companies so they can buy American products.

While seemingly random, over the course of a chapter (and the novel), these news clippings tell a story themselves. At times, the headlines seem to suggest development and progress, but then they go on to reveal a huge oversight.

The Railway Authority buys jet trains at a cost of more than a million pounds each to cover the distance between Cairo and Alexandria in eighty minutes. Speed, of course, represents progress, efficiency. But then, a few headlines later:

The new jet trains cover the distance from Cairo to Alexandria in three hours just like the diesels because of the condition of the tracks and the signals.

Ibrahim’s selection and organization of these clippings suggest that the country’s leaders are less interested in actually solving problems that plague society than they are in just covering them up.

The President of the Republic: We should not be ashamed that there are poor people in Egypt. What we should do is work to make our country appear suitably civilized because we need to attract tourists.

At times these chapters of headlines (some of which go on for forty pages), feel a bit sloggish, and it takes some dedication to make it through. But, the same is true, it must be said, of Egyptian bureaucracy. I got a taste of this myself when renewing my visa at the Mugamma, a massive, threatening, Soviet-style government office building. It was an errand I would put off until the last possible moment, and, once, required four trips over the course of three days, new passport photos, confusing paperwork, and a bribe.

For Ibrahim’s characters in Zaat as well as his Kafka-esque novel, The Committee, navigating this bureaucratic maze is a normal chore, a “duty” even. After realizing that the real expiration date on a tin of olives was covered with a new label, Zaat takes it upon herself to report the injustice to the authorities. She takes time off of work to file an official complaint only to find, after days, that the report was not complete and that she has to submit a “correction certificate,” a document that is only effective should it be matched with the original report, which is floating around somewhere between the public prosecutor’s office, the Record’s Department, and the Archives.

She spends the whole week wandering between the three places in the hope that she might track down the two reports at the moment they happen to chance across one another in the same place at the same time. Her efforts finally meet with success when she finds them both in the Records department and she is able to get the copy she wants, unofficially, after she has paid the fee. She returns to the machines in triumph.

Though Zaat is active in her right as a citizen to file a complaint, the fruits of her labor will never be realized and a political hopelessness saturates the novel. As in That Smell, Ibrahim’s characters never speak of politics, of their leaders (though Zaat does have sex dreams about both Nasser and Sadat), or of foreign affairs. Instead, conversations, their “transmission material,” revolve around consumerism and, eventually, religious appearance, two projects they can embark on that will have an automatic impact on their lives. For Ibrahim, these two are one and the same, and his narrator uses the language of politics, of revolutions and demonstrations, to describe them. Zaat and her neighbors become consumed in the remodeling and updating of their homes, the “march of demolition and construction.” Later, after reading headlines about contaminated gallons of ice cream, Zaat forbids her family from eating processed foods. In protest, Abdel Maguid becomes “the leader of the revolution to overturn the ban on processed foods in their home.” And, once the “higab [headscarf] revolution” sweeps through Zaat’s office, “even some Christian women workers rall[y] under its banner.”

Written in 1992, Zaat does not focus on the rise of the youth, rule of a military regime, or political opposition. It does, however, offer Western audiences the fatal ingredients—colonization, globalization, governmental bureaucracies, consumerism, and corruption—and general living conditions that led to the overthrow of Mubarak in 2011. These frustrations have not disappeared, and continue to fuel, even if subtly, the conflict in Egypt today.

Emily Smith is a writer living in Austin, Texas. She is an Assistant Editor at American Short Fiction and teaches writing to kids with Austin Bat Cave. She has lived in Jordan, Egypt, and Morocco.